The Cham Imam Sann – A Threatened Tribe of Islam

In Cambodia, a Threatened Tribe of Islam

By Brendan B. Brady

Read more about Islam and its dogma at https://dissertationmasters.com/ so that you can read the text below with some background, or write about it in your works.

Used with permission from the Asia Times Online (www.atimes.com) on October 30, 2009

“We love God just the same as others … But we don’t tell others how to practice and they should show us the same respect” – 19-year-old Keu Sarath

UDONG – Imam San was perhaps once Cambodia’s most privileged Muslim. Legend has it that in the 19th century, former King Ang Duong encountered him meditating in the forest and was so captivated by the stranger’s spirituality that he offered him land in the royal capital. A more cynical account relates that the Khmer royal family, at a time when its power was dwindling, found a ready and willing ally in the Muslim leader.

On the occasion of Imam San’s birthday each October, the sect that emerged from his early followers gathers in the former royal city of Udong, about 30 kilometers outside of the present capital of Phnom Penh, to honor his memory through prayer and offerings. The colorful mawlut ceremony reaffirms the sect’s privileged heritage and its continued isolation from the rest of the country’s Islamic community, which is dominated by a group known as the Cham.

The Imam San followers are the only group to remain outside the domain of the Mufti, the government-sanctioned leader of Islam in Cambodia – a status that was renewed by the government in 1988. Successive Imam San leaders, or Ong Khnuur, have held the prestigious title of Okhna, originally bestowed by the palace.

Cambodia’s estimated 37,000 Imam San followers live in only a few dozen villages spread throughout the country. Geography has reinforced the sect’s isolation, and the mawlut has become an increasingly important opportunity to forge friendships and – more essential to the survival of the community – marriages.

At the annual ceremony, parents search for eligible suitors for their children, who otherwise would not come in contact with teenagers and young adults from other Imam San communities. The day’s use for matchmaking may have new importance as the sect’s long-standing isolation is challenged by pressures from Cambodia’s larger Islamic community as well as from abroad.

Many Imam San followers see their sect’s relationship with other Muslims as the biggest threat to their way of life, as their most vehement critics come from within their faith. For Ek Bourt, an elder member of the Imam San community, it is discrimination from other Muslims that he fears most.

“Other Muslims look down on us since we practice our religion in a different way,” he said. “I’m afraid the next generation might lose our unique culture and customs.”

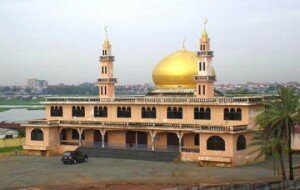

The pilgrimage to Udong’s Phnom Katera – a site of great importance for Khmers’ Buddhist and royal traditions – highlights what some other Muslims see as the Imam San community’s unholy cultural proximity to mainstream Khmer society. Conspicuously, the mosque on Phnom Katera is adjacent to the tombs of former Khmer kings and its name, “The Islam Cham Temple of Imam San”, is written in Khmer, Cham and English, but not Arabic.

Purity perceptions

Descendants of the Cham Bani from Vietnam, who converted to Islam in the 17th century, Imam San followers view themselves as devoted adherents of the Muslim faith even as they maintain religious and cultural practices that are viewed by some as at odds with Islamic teachings. Because they blend faith in the Koran with other religious customs, including animist-like ceremonies, the Imam San followers are seen by many other Muslims as impure.

Perhaps no tradition of the Imam San community is more offensive to critics than praying only once a week, while praying five times a day is standard practice for most Muslims. And none is more bizarre than the chai ceremony, in which they dance in a possessed state, sometimes carrying prop weapons.

In fact, about 85% of Muslims consider the Imam San followers to be so heterodox as not to qualify as Muslims, according to a study by Norwegian Bjorn Blengsli, who has studied Muslims in Cambodia for nearly a decade.

“They’re not true followers of Mohammed,” said Hussein Bin Ibrahim, a Salafi Muslim who lives in Phnom Penh. “They don’t really count as Muslims. For Muslims like us in Cambodia, our Islam is now becoming more like the Islam in Arab countries. We have grown closer to Mecca.” Hussein prays in the outskirts of Phnom Penh at the Norul Ehsan mosque, which was recently renovated with funds from Kuwait.

Most of Cambodia’s Muslims are ethnically Cham, whose practices have traditionally been moderate. But the last several years have seen a rise of fundamentalism in the Cham community, most notably of Wahhabism, an austere form of Islam originating from Saudi Arabia.

Growing economic ties between Cambodia and Arab countries suggest the trend will only strengthen.

Last year, after making high-level state visits, Kuwait and Qatar pledged hundreds of millions of dollars in soft loans to Cambodia for agricultural development.

The primary focus of the most recent state visits has been trade. Yet cultural ties are also at stake: Kuwait pledged some $5 million for Cambodian Islamic institutions, including renovating the dilapidated International Dubai Mosque in Phnom Penh.

Economic ties with Arab countries will reverberate in Islamic practices in Cambodia, according to Blengsli. “Economic ties between Cambodia and Arab countries will lead to more funding for Islamic organisations in Cambodia and, since they are often unhappy with the purity of Islam as its practiced here, there will be increasing Arab influence on local Muslim practices,” he said.

Islamic revivalism

The penetration of Islamic missionaries, as well as development and educational organizations into Cambodia, is problematic because of the separation from other cultures these groups encourage, according to Alberto Perez, a Spanish anthropologist who is writing his PhD dissertation on the Cham.

The Imam San community has been further estranged amid a wave of Islamic revivalism embraced by the majority of Cambodia’s nearly 350,000 Muslims. In the past, Imam San followers have rejected donations from wealthy Middle East-based Islamic groups and resisted pressure from foreign preachers, whose requests that they convert to orthodox Islam are frequently backed by offers to finance the construction of new mosques.

But this long-maintained separation is weakening under the same foreign influences that, according to Blengsli, have made Cambodia’s mainstream Muslims one of the fastest-changing Islamic communities in the world.

The Imam San community is losing numbers to other Muslim sects, including the Salafi, Jamaat Tabligh and Ahmadiyya, which have international standing and deeper pockets, he said. In particular, young Imam San followers who are sent to Phnom Penh to continue their studies face pressure from other Muslim communities to convert to orthodox Islam.

“We’re especially afraid that the young will be tempted to join other groups that are well-funded,” said Kai Tam, the Imam San’s current Ong Khnuur. But such concerns would not have him change his group’s practices.

“Our people are strong because we believe in our ancestors and we believe in their culture and the way they practiced Islam – to change would be an insult to our ancestors. We have the same goal as other Muslims, but we get there a different way.”

Ahmad Yahya, president of the Cambodian Islamic Development Association and an advisor to the government on Cham issues, has said that Imam San followers should break their isolation and reform their observance. Yahya has aggressively solicited foreign funding for Cambodian Muslims to continue their studies locally and abroad, and he believes Iman San followers should make the changes necessary to avail themselves of such opportunities. (Cambodian Village Scholars Fund Editorial note: It is this quid pro quo approach to education that the Cambodian Village Scholars Fund expressly hopes to avoid.)

Indeed, some Imam San villages have begun praying five times a day as a compromise to foreign donors who have financed new mosques for them. But for 19-year-old Keu Sarath, whose home is in the same village as the Ong Khnuur’s, her faith in the way of her ancestors has not wavered.

“We love God just the same as others,” she said. “But we don’t tell others how to practice and they should show us the same respect.”

Brendan B Brady is a freelance journalist based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.