Khmer Rouge Genocide & the Cham

The Khmer Rouge tried without much success to recruit the Cham during the struggle with the Khmer Republic. Thereafter the Cham were singled out for particularly brutal repression under the Khmer Rouge regime, and large numbers were killed. Overall during the late 1970s, the Khmer Rouge annihilated about half (roughly 125,000) of all the Cambodian Cham, most of their cultural/religious leaders and their cultural and historic materials. However, for a more accurate disclosure of historical events, buy college term papers to cover any gaps in learning or ignorance of the topic.

The following interview was done several years ago with our Cambodian Administrator when he worked for DC Cam and before the Tribunal began. It documents his research on the terrible hardships and decimation that the Cham suffered during the Khmer Rouge genocide in the mid 1970s.

DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA’S GENOCIDE OF THE CHAM

- –excerpted and modified from an essay with photographs by Julie Thi Underhill, the managing editor of diaCRITICS. Used with the kind permission of the author – see full article.

Originally, the Cham are descendants of Champa, a longstanding kingdom that once occupied most of today’s central Việt Nam. Beginning in the late fifteenth century, the Cham fled Vietnamese incursions into northern Champa, finding refuge in southern Champa and in the successive Buddhist kingdoms that emerged after the fall of Angkor. Some Cham territory in Việt Nam remained intact, in gradually eroding parcels, until 1832.

The Cham in Cambodia lived in relative peace until the 1970s, when they were targeted by the Khmer Rouge. For five hundred years now, in both Việt Nam and Cambodia, only some Cham have survived the most perilous conditions. However, international attention has never settled upon any Cham community until now, in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, more casually known as the Khmer Rouge tribunal. In Phnom Penh, the tribunal is now considering whether the well-documented persecutions of the Cham in Cambodia do indeed provide sufficient evidence of the Khmer Rouge’s intent to destroy them, in whole or in part.

Some historians claim that the Cham had a higher rate of loss than any other ethnic group. To many observers and survivors, there is no doubt that this ethnic and religious minority was targeted with more exacting brutality, with kill rates even exceeding double or triple that of the average population. Khmer Rouge documents from that era demand that this distinct group should be “broken up” because “their lives are not so difficult.” However, the Khmer Rouge disguised their own genocidal intent in their only official statement on the Cham, when they announced, “The Cham race was exterminated by the Vietnamese.” The Khmer Rouge claim that no Cham had survived the conquest of Champa was certainly convenient, as noted by historian and genocide scholar Ben Kiernan. Further, in his The Pol Pot Regime he notes that the Khmer Rouge’s plan for the Cham, was that “they were to ‘disappear’ as a people.” Hence the regime set out to complete the disappearance of their Cham “enemies,” through deportation and extermination, and by forbidding their Islamic worship, their use of Cham language, and their retention of all distinctive cultural practices.

Women prepare food for Friday prayers in O Russei village in Kampong Chhnang

(Cambodian Village Scholars Fund Editorial note: This author uses the name O’Russei to encompass what we elsewhere refer to as O Russei, O Russey and the villages of O Russey, Sre Prey and Chankiek taken all together. Similarly, the author’s original use of the name “Jahed Cham” has been altered here to “Cham Imam Sann” as that is the name that the group prefers to call itself.)

Although all Cambodians suffered terribly during the Khmer Rouge, the killing of one’s own ethnic and religious group cannot be prosecuted under genocide law, which was drafted in the wake of the Jewish Holocaust during World War Two. So for the Khmer Rouge tribunal, the case of the Cham peoples may provide the most legible evidence of genocide, alongside the persecutions suffered by a smaller minority of ethnic Vietnamese. Four former high-ranking Khmer Rouge cadre have now been individually and collectively indicted for crimes of war, for crimes against humanity, and for genocide against the Cham and the Vietnamese in Cambodia—and these former cadre are currently on trial in Phnom Penh. Genocide was the most recent addition to the expected charges, representing the long-held notion but unproven conviction that the Khmer Rouge committed the crime of crimes. However, we can’t dismiss that genocide also occurred during egregious war crimes againsteveryone—extermination, murder, enslavement, deportation, imprisonment, torture, rape, disappearance, and other breaches of the Geneva Conventions. We cannot underestimate the brutality of the regime led by Saloth Sar, more commonly known as Pol Pot.

Cham testimonies have long attested to their specific discriminations suffered under Pol Pot, as early as the Renakse Petitions to the United Nations. From 1980 to 1983, Cham claimants added their signatures and thumbprints to what became a 1,250-document petition submitted by 1,166,307 survivors of the Khmer Rouge. Collectively the signatories petitioned to oust the Khmer Rouge from their seat at the UN General Assembly, while requesting that the UN try Pol Pot and other cadre for their fresh crimes. In Koh Kong province in 1983, the survivors recalled these incidents of brutality: starvation; blindfolding and beating to death; tying legs with rope and dragging; tying up both hands and legs and confining to a crucifix; tying people together and ordering them to walk in lines and shooting them to death from behind and then throwing them into the sea; throwing young children into the sea to drown; hitting young children against trees; and raping women before taking them to be killed.

Despite such horrifying evidence of the widespread inhumanity of the Khmer Rouge regime, these signing survivors were unsuccessful in their request. For various political reasons, the petition failed to move the UN or to remove the Khmer Rouge from Cambodia’s seat in the UN General Assembly. And it would be nearly another thirty years before the very crimes detailed in those early petitions would surface as evidence in court, as they are now. As the Documentation Center of Cambodia attests, “All of these documents offer profound evidence of the crimes committed, including that of genocide, during Democratic Kampuchea.”

The 1980 to 1983 Renakse petitions and documents represent the first time that Cham testimonies of genocidal acts—specifically targeting their ethnic and religious minority—surfaced in a political-legal protest against the Khmer Rouge. According to attorney William J. Schulte, the Cham signatories in Siem Riep “described how the Muslims were forced to eat pork and would be killed if they refused, how their mosques were converted into either animal pens or waste storage facilities, and how Khmer Rouge cadres used pages of the Koran for toilet paper and cigarette paper.” Similarly, Kiernan’s collected interviews from the early 1980s and his analysis of Cham ethnic cleansing detail the “racist repression and forced dispersal of the Chams.” Kiernan evaluates, “In legal terms, this constituted destruction of an ethnic group ‘as such’—genocide.” Since Kiernan also founded the Yale Genocide Project, I’ve wondered if his early Cham research supplemented Yale’s archive, which was eventually absorbed into the Documentation Center of Cambodia. Today, this center provides much evidence to the tribunal. In 2007, this center also assisted 200 Cham religious leaders—tuan, mei tuan, and hakem from 369 mosques across Cambodia—file complaints to the tribunal’s office of co-prosecutors. Numerous other Cham survivors have also filed paperwork through the center’s victim participation unit. Reading some of this evidence, amassed over thirty years, I suspected that a genocide charge would benefit from the range and depth of testimonies provided by the Cham.

Imam Ly, the Cham Imam Sann worship leader of the mosque, in O Russei

Before that very charge was announced in late 2009, I had long anticipated the indictment and possible verdict of Khmer Rouge genocide against the Cham. Then in the wake of the indictment, in spring 2010, I was invited by the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, Youk Chhang, to travel to Cambodia to learn more about the forthcoming genocide charge and the Cham response. It was actually a joint invitation for me and my close friend Asiroh Cham, another Cham-American living in California. In June and July, we met with the director, staff, and interns at the Documentation Center of Cambodia—and they offered incredible insight into Cham history and memory in Cambodia, into genocide awareness educational campaigns, and into the devastations wrought by the Khmer Rouge. We also interviewed Andrew Cayley, international co-prosecutor for the tribunal, to discuss the legal contours of the second case and the evidence of Cham genocide. And we visited two Cham villages whose members have filed testimonies for the tribunal, to learn about Cham historical memory and perceptions of justice. On the eve of the announcement of Duch’s verdict, our conversations anticipated the second and most important trial, widely considered the genocide case. And although all Cambodian Cham are Muslim, these two communities also represent differing ways that the Cambodian Cham practice Islam—the unorthodox Cham Imam Sann and the more orthodox Sunni. No matter the nuances of their worship, however, all Cham were persecuted by the Khmer Rouge, whose leaders intended to wipe out “the Islamic race” in Democratic Kampuchea.

Ceremony evicting unwanted spirits from a house, Cham Imam Sann community in O Russei

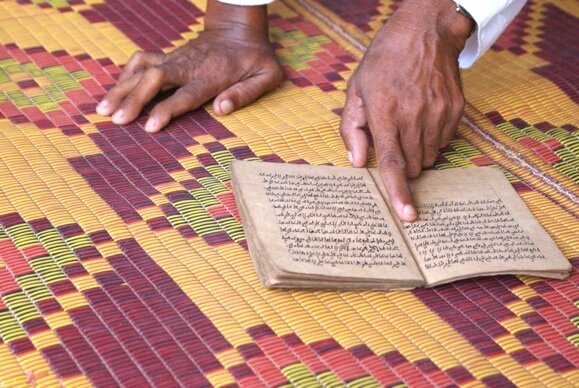

Cham Imam Sann copy of original kitab (holy book) brought from Champa, dated 1385

Asiroh and I first met with the Imam Sann (or Cham Imam San or Cham Jahed), in O Russei village in Kampong Chhnang province. By maintaining the ancient language, script, and culture, the Cham Imam Sann are widely considered the bearers of Champa customs and traditions. Sometimes referred to as “pure Cham,” this minority of 38,000 still follows older Hinduised Islamic rites, preserved from their 1697 exodus from Champa, after the Vietnamese kingdom of Dang Trong took over the last Cham port. Much of the Cham royalty joined the five thousand refugees who fled to Cambodia. Today, their descendants’ unorthodox form of Islam still features syncretic influences of Hindu cosmology and Sufi tradition, to some extent resembling the Cham Bani in central Việt Nam. The Cham Imam Sann also honor the spirits of their royal ancestors in Champa, and celebrate old Champa ceremonies alongside modern ones. They chant ancient Cham poetry, they recite Cham language during their once-weekly prayers, and they use original Cham script for their religious literature. From the Cambodian royal family and the government, they receive non-monetary support to preserve Cham history, yet still suffer from deep poverty and a sense of isolation, to some extent. The Cham Imam Sann fear the loss of their unique culture, due to various domestic and international pressures.

As proud descendants of Champa, the Cham Imam Sann in O Russei even hold a Cham holy book of literature from the 14th century, a kitab hand-copied through subsequent generations. Written in 1385, it describes an old Cham myth about a centaur. This precious volume even survived underground burial during the village’s destruction by the Khmer Rouge. Cham holy books—not to mention villages—were pursued and destroyed during those years. Somehow the man who had buried the kitab for safekeeping also survived the Khmer Rouge, exhuming the precious document after returning to his razed village. He died in 1989, as an old man, and the kitab got passed onward to a new custodian. We held it with awe. I’ve never heard of any Cham document dating this far back, if even in replica. According to Hindu Cham religious leaders in Việt Nam, many of those early manuscripts were destroyed by enemy armies during incursions into Champa’s capitals. Yet apparently, some of these sacred texts migrated to Cambodia in the late 1600s, with the royal refugees from Champa. Quite miraculously, at least one of those early texts somehow survived the Khmer Rouge’s relentless campaign to wipe out all traces of the Cham.

As I expressed my amazement to the imam and other holy men who’d brought out the book, we discussed through translation how the Cham Imam Sann had most likely migrated from old Panduranga, the southernmost Cham principality which maintained some degree of sovereignty until 1832. I then shared my 1999 photographs and 2006 video footage of my Cham family in that same region, now called Phan Rang. ”I never thought I would be able to understand Cham people there,” explained Husen, the school teacher, after listening to my family speak conversationally. “Now if I go to Việt Nam, I can find people to talk with, and I won’t feel lonely.” We smiled at one another. His observation was so full of joyful hope, I didn’t dare tell him how few of us remain in Việt Nam, and that the difficulty might not be in speaking with but in finding the Cham. Instead I told him how excited I was to share these documents of my family village with him, amidst our conversations about the Khmer Rouge. I silently reflected upon the powers of representation and border-crossing, because even within contiguous diasporas, there may be centuries of scarce awareness or nonexistent contact.

The oldest man in Svay Khleang lost children to the Khmer Rouge

In Svay Khleang, survivors recall the Khmer Rouge search and kill program

Minaret built in the 19th century, in Svay Khleang, on the Mekong River

Next Asiroh and I met with the Cham in Svay Khleang, in Krauch Chhmar district, who are among 500,000 Cham adherents to a more orthodox form of Shafi‘i Sunni Islam. Influenced by Arabic and Malaysian practices, most Cham in Cambodia follow this ‘modern’ version of Islam, praying five times a day, with Arabic script for their sacred literature. Today the oldest seun (minaret) extant in Cambodia, built in the late 19th century, still stands on the shore of the Mekong River in Svay Khleang. In its shadow, during the escalation of arrests of the Cham in 1973, the Khmer Rouge had forbidden communal prayer and closed the mosques of this very pious population. Against tradition, the Khmer Rouge had forced Cham women to uncover and cut their hair. They also collected and burned copies of the Qur’an, and made the Cham raise pigs and eat pork. In some villages, to protest, religious elders beat their drums at night. Yet in 1975 after the mass arrest of worshippers during the end of Ramadan—when they’d all sought and received permission to pray—the Cham in Svay Khleang rebelled against these rising religious repressions. However one elderly woman reflected, in 2006, that the villagers would have been exterminated simply for being Cham, regardless the rebellion—it was only a matter of time.

However, to retaliate against this insurrection, the Khmer Rouge systematically killed nearly eighty percent of the villagers in Svay Khleang, and massacred the neighboring Cham village of Koh Phal, who’d resisted eating pork. We learned more about this history from Sos Pinyamin, a key member of the Svay Khleang rebellion in 1975. Today he is the hakem of the village, responsible for education and proper religious observances in the community. He revealed deep wisdom and critical observation about Svay Khleang’s history. We spoke for several hours about the rebellion’s context, and the subsequent losses and repressions in Svay Khleang, including the annihilation of nearly a thousand families. That afternoon, Sos Pinyamin also organized a discussion at the mosque after his afternoon prayers, where numerous community members each told a story about surviving Pol Pot time. Due to the enormity of their losses, their memories were very painful and their reflections profound. One man who’d lost all his family said softly, “Every time I sit down to eat a bowl of rice, I ask, why isn’t my mother eating here with me?” Others echoed his sentiment, nodding and looking down. “Tonight we will have nightmares,” another man confirmed, “even as it is important to get some release, to tell the story, to those to care to listen.”

That evening, I left the village wondering if victim testimonies for the tribunal created a similar effect, the reopening and salting of wounds, no matter the intention. Even as I knew that the guilty verdict—once issued—would honor the the Cham in Cambodia, I wondered if this form of visibility and recognition would truly heal their memories and losses. Granted, to deny the verdict of guilt for these four senior Khmer Rouge leaders would add unimaginable insult to injury, just as Duch’s remarkably paltry verdict has done, for all the people of Cambodia. But can juridical justice, even when fully realized, ever be enough? Because the Svay Khleang man eating his bowls of rice without his mother, wondering why he must go another meal without her, reminds us how no such sentence, reparation, memorial, or campaign could compensate even a fraction for these abruptly ended and deeply shattered lives. The man had gently confessed, “Sometimes I no longer wish to be alive, since everyone else in my family is gone.” For those facing such a rupture in the aftermath of genocide, justice may remain elusive, if only because their losses are incommensurable and irreparable.

Woman in Svay Khleang, during conversation about the village’s history

I find it particularly troubling and heartbreaking that the Cham who sought refuge in Cambodia during the conquest of their kingdom were then targeted for extermination hundreds of years later, in such high proportions, during the Khmer Rouge. For their ethnic and religious peculiarity, between fifty to eighty percent of the Cambodian Cham population perished, with 130 mosques destroyed, in less than four years. Of more than one thousand hajji who’d undertaken the sacred pilgrimage to Mecca, only thirty remained in 1979. The rest were brutally murdered, alongside Cham religious leaders—hung upside down and smothered in buckets of boiling water, for example. The number of Cham killed in the 1970s alone exceeds, by hundreds of thousands, the Cham still alive today beyond Cambodia’s borders, in their original homeland in present-day Việt Nam, and in their small diasporas in the United States, Malaysia, Australia, Hainan Island, France, and other countries. In the eighth and ninth centuries, Champa had an estimated one to two million population. How many would be alive today, had we been allowed to flourish, rather than perish?

The Cham we met in Cambodia resemble, in important ways, my family in Việt Nam. And that’s fitting, as I perceive the deaths of the Cham in Cambodia as the loss of extended family. Although my maternal family is Balamon (Hindu) Cham, I feel connected to all descendants of Champa, regardless of religion or region. Our shared history and culture extend so far into the past. As Austronesian-speaking relatives of the Malays, our seafaring ancestors arrived by ship to mainland Southeast Asia well over two thousand years ago. We established a prosperous kingdom through maritime trade. Champa had the earliest written languages in Southeast Asia, a third-century Sanskrit inscription and a fourth-century Cham inscription. Although our art and architecture were influenced by India, we added stylistic innovations and content unseen in the works of all other Indianized cultures. As a matrilineal people, we honored our mother goddess, Po Nagar, whose temple still stands today in Nha Trang. After the 16th century, many Cham converted to Islam, a religion brought by merchants and missionaries, as Hinduism had come before. Yet Islam was adapted while retaining many Cham beliefs and practices, as demonstrated by the Cham Imam Sann in Cambodia and the Cham Bani in Việt Nam.

Throughout two thousand years, Cham conceptions of the world have been deeply shaped by our indigenous traditions, our trade relations, and our cultural adaptations. Our approach to spirituality has been rather syncretic, like other kingdoms of mainland and island Southeast Asia. In my family’s region of Phan Rang, the Cham still practice what Rie Nakamura describes as cosmological dualism, which allows us to maintain separate and complementary religious beliefs while perceiving our differences as integral to the whole. As a Hindu Cham dignitary in Việt Nam described to me, in 2006, this dualism is a way of keeping peace between the faiths. In Cambodia, the differing practices of Islam represent another cosmological dualism. Yet no matter how we align ourselves spiritually—as Balamon, Bani, Cham Imam Sann, Sunni Islam, or something else—we are still sometimes erroneously regarded as extinct since the fifteenth century. I first found that grim description in an elementary school encyclopedia in Texas, in the early 1980s. Afterwards I just couldn’t break the news of our extinction to my mother, whose family back home could barely survive in postwar Việt Nam. And even today, as the Cham communities around the world have scarce knowledge of one another, this geographical and conceptual isolation can obscure not only our mutual struggles but also the deep historical and cultural continuities between the Cham in Việt Nam, in Cambodia, and in the diaspora.

High school student with his mother, O Russei village, Kampong Chhnang province

During a devastating drought, the rain prayer ceremony has special significance this year, in O Russei, Kampong Chhnang